Northern Shrimp

Life History

Northern shrimp (Pandalus borealis) is a crustacean located in the cold waters of the Northern Hemisphere. On the U.S. Atlantic coast, the Gulf of Maine is considered the southernmost extent of the species range. Northern shrimp are hermaphroditic, maturing first as males at roughly 2 1/2 years of age and then transforming to females at about 3 1/2 years. Female shrimp may live up to five years old and attain a size of up to three to four inches in length. Differences in size at age by area and season can be ascribed to temperature effects, with more rapid growth rates at higher temperatures. Differences in size at age from year to year, and in size at sex transition, have been attributed to both environmental and stock density effects.

Spawning takes place in offshore waters during the late summer. By early fall, most adult females extrude their eggs onto the abdomen. Egg-bearing females move inshore in late autumn and winter, where the eggs hatch. Northern shrimp are an important link in marine food chains, preying on both plankton and benthic invertebrates and, in turn, being consumed by many important fish species, such as cod, redfish, and silver and white hake.

Commercial & Recreational Fisheries

Historically, northern shrimp have provided a small but valuable fishery to the New England states. The fishery is seasonal in nature, peaking in late winter when egg-bearing females move into inshore waters and ending in the spring under regulatory closure.

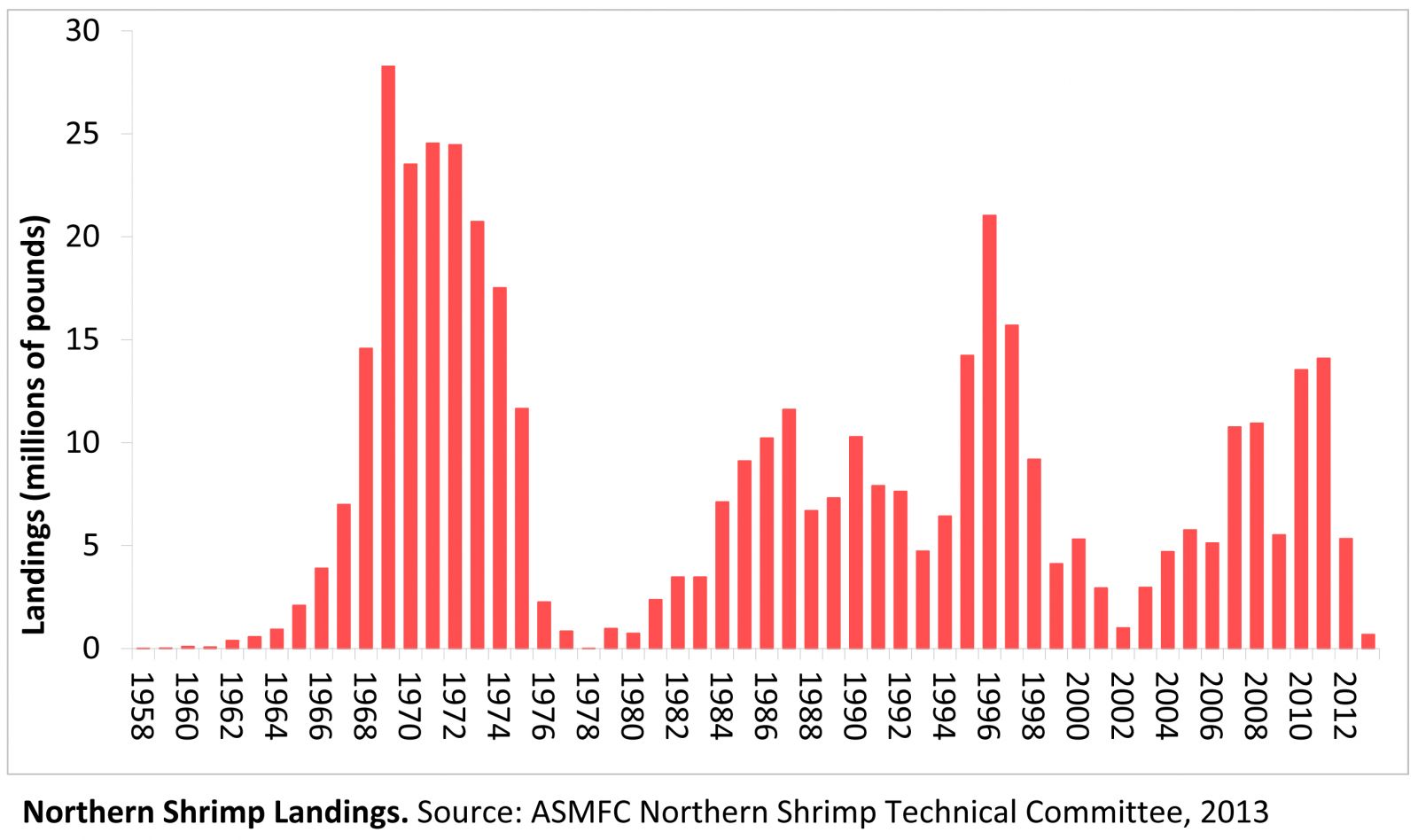

The commercial fishery began in the late 1950s and soon experienced an incredible expansion in landings, peaking in 1969 at 28.3 million pounds. Over the next decade, landings dropped precipitously and the fishery closed in 1978 due to stock collapse. The fishery reopened in 1979 and produced stable landings through the 1990’s (peeks in landings occurred in 1987 and 1996 at an estimated 11.6 million pounds and 20.1 million pounds, respectively). In 2002, landings declined to 992,250 pounds, the lowest levels observed since the 1978 closure, but landings again increased to an average of 7.9 million pounds during 2003-2012. In 2010, however, the proposed 180-day season was cut short with 13.5 million pounds landed due to the industry exceeding the recommended landings cap for that year, and concerns about small shrimp. The season was similarly cut short in 2011, and the 2012 season was further restricted with gear-specific seasons, landings days, and trip limits. The total allowable catch (TAC) was set at 4.9 million pounds and would close when the projected landings reached 95% of the TAC. The season closed on February 17, resulting in a 21-day trawler season and a 17-day trap season.

The 2013 season, which was classified as a “do no harm” fishery, resulted in a fishing mortality rate (0.53) above the target (0.38). This was despite the fact that only 49% of the total allowable catch was harvested (676,935 pounds of 1.39 million pounds). Due to recruitment failure and a collapsed stock, a fishery moratorium has been in place since 2014.

Stock Status

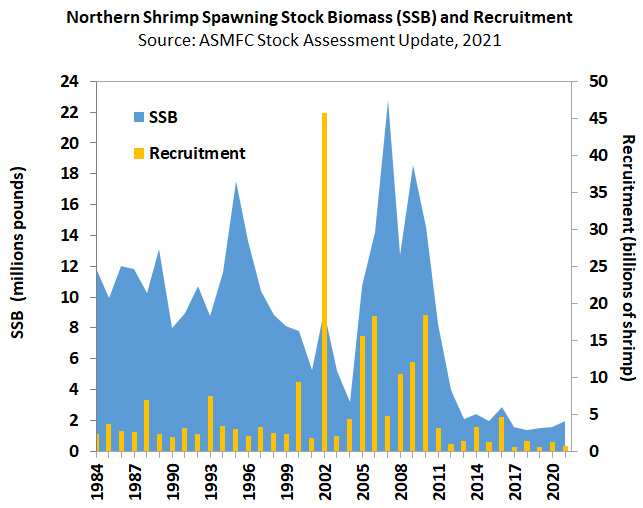

The 2024 Stock Assessment Update indicates the northern shrimp stock in the Gulf of Maine remains in a depleted condition. Biomass is at extremely low levels and has been since 2013. Spawning stock biomass (SSB) in 2024 is estimated at 279 mt, the lowest in the time-series and well below the time-series median of 4,732 mt. Recruitment also remained low for 2022 and 2023, a continuation of the series of below-average year classes for the last ten years. Fishing mortality has been very low in recent years due to the moratorium, but high levels of natural mortality and low recruitment have hindered rebuilding.

Recruitment of northern shrimp is related to both SSB and ocean temperatures, with higher SSB and colder temperatures producing stronger recruitment. Ocean temperatures in western GOM shrimp habitat have increased over the past two decades and have sustained unprecedented highs in the past ten years. While spring bottom temperatures and winter sea surface temperatures declined somewhat in 2023, , temperatures are predicted to continue rising as a result of climate change. This suggests an increasingly inhospitable environment for northern shrimp and the need for strong conservation efforts to help restore the stock. The Northern Shrimp Technical Committee considers the stock to be in poor condition with limited prospects for the near future.

Atlantic Coastal Management

Northern shrimp, Pandalus borealis (top), and two species of striped shrimp (P. montagui and Dichelopandalus leptocerus bottom). Photo by Cinamon Moffett, University of Maine.

The Commission’s Northern Shrimp Section is comprised of the states of Maine, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts. The original Fishery Management Plan was adopted by the Commission in 1986. Amendment 1 (2004) established biological reference points for the first time in the shrimp fishery and expanded the tools available to manage the fishery. Management of northern shrimp under Amendment 1 resulted in a rebuilt stock and increased fishing opportunities. However, early season closures occurred in 2010 and 2011 because landing rates were far greater than anticipated. Furthermore, untimely reporting resulted in short notice of the season closures and an overharvest of the recommended total allowable catch (TAC).

To address these issues, Amendment 2 (2011) completely replaced the FMP and provided management options to slow catch rates throughout the season, including trip limits, trap limits, and days out of the fishery. Additionally, the amendment modified the fishing mortality reference points to include a threshold level, included a more timely and comprehensive reporting system, and allowed for the initiation of a limited entry program to be pursued through the adaptive management process. Addendum I (2012) clarified the annual specification process, introduced a research set aside provision, and allocated the TAC with 87% for the trawl fishery and 13% for the trap fishery based on historical landings by each gear type.

Due to the stock collapse in 2013, the Northern Shrimp Section implemented a commercial fishing moratorium for the 2014 fishing season which it has maintained through 2024. In 2017, the Commission approved Amendment 3 which is designed to improve management of the fishery in the event that it reopens. Specifically, the Amendment refines the FMP objectives and provides the flexibility to use the best available information to define the status of the stock and to set the total allowable catch. Furthermore, the Amendment implements a state-specific allocation program to better manage effort in the fishery; 80% to Maine, 10% to New Hampshire, 10% to Massachusetts. The amendment also strengthens catch and landings reporting requirements, implements mandatory use of size sorting grate systems to minimize harvest of small (presumably male) shrimp, incorporates accountability measures, specifies a maximum fishing season length, and formalizes fishery-dependent monitoring requirements. The following year, the Section approved Addendum I, which provides states the authority to allocate their state-specific quota between gear types.

Given the continued poor condition of the stock, in December 2023 the Section initiated Draft Amendment 4 to the Northern Shrimp FMP which considers options for setting multi-year moratoria and implementing management triggers. Management trigger options include biologic and environmental triggers comprised of indicators that would signal improvement in stock conditions and the potential to re-open the fishery. In December 2024, the Section extended the moratorium on commercial and recreational fishing through 2025 and approved a research set-aside quota of 26.5 mt (or approximately 58,400 pounds) for the pilot industry-based winter sampling program. This moratorium was set in response to the low levels of biomass and recruitment and the fact that, should recruitment improve, it would take several years for those shrimp to be commercially harvestable.

Management Plans & FMP Reviews

- Northern Shrimp Addendum I to Amendment 3 (November 2018)

- Northern Shrimp Amendment 3 (October 2017)

- Northern Shrimp Addendum I (November 2012)

- Amendment 2 to the Interstate Fishery Management Plan for Northern Shrimp (October 2011)

- Amendment 1 to the Fishery Management Plan for Northern Shrimp (June 2004)

- Fishery Management Plan for Northern Shrimp (October 1986)

Stock Assessment Reports

- 2024 Northern Shrimp Stock Assessment Update (Dec 2024)

- Northern Shrimp 2023 Data Update (Nov 2023)

- Northern Shrimp 2022 Data Update (Nov 2022)

- Northern Shrimp Stock Assessment Update 2021 (Dec 2021)

- Data Update for Gulf of Maine Northern Shrimp (Nov 2019)

- 2018 Assessment Report for the Gulf of Maine Northern Shrimp (Nov 2018)

- 2018 Northern Shrimp Benchmark Stock Assessment and Peer Review Report (Oct 2018)

- Stock Status Report for Gulf of Maine Northern Shrimp (Nov 2017)

- Stock Status Report for the Gulf of Maine Northern Shrimp (Nov 2016)

- 2015 Stock Status Report for Gulf of Maine Northern Shrimp (Nov 2015)

- 2014 Stock Status Report forthe Gulf of Maine Northern Shrimp (Nov 2014)

- 2014 Stock Status Report for Gulf of Maine Northern Shrimp (Nov 2014)

- 2013 Assessment Report for Gulf of Maine Northern Shrimp (Nov 2013)

- 2012 Assessment Report for Northern Shrimp (Jan 2012)

- 2011 Assessment Report for Northern Shrimp (Jan 2011)

- 2010 Assessment Report for Northern Shrimp (Jan 2010)

- 2009 Assessment Report for Northern Shrimp (Jan 2009)

- 2008 Assessment Report for Northern Shrimp (Jan 2008)

- 2007 Assessment Report for Northern Shrimp (Jan 2007)

- 2006 Assessment Report for Northern Shrimp (Jan 2006)

- 2005 Assessment Report for Northern Shrimp (Jan 2005)

- 2004 Assessment Report for Northern Shrimp (Jan 2004)

- 2003 Assessment Report for Northern Shrimp (Jan 2003)

- 2002 Assessment Report for Northern Shrimp (Jan 2002)

- 2000 Assessment Report for Northern Shrimp (Jan 2000)

Meeting Summaries & Reports

Press Releases

- Northern Shrimp Section Approves Pilot Winter Sampling Program and Draft Amendment 4 for Public Comment (December 2024)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section and Panel to Meet December 12: Section to Consider Draft Amendment 4 for Public Comment and Set 2025 Specifications (November 2024)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section to Meet to Consider Next Steps in Amendment 4 Development: Advisory Panel & Technical Committee to Discuss Industry-Based Research Program (September 2024)

- States Schedule Public Hearings on Northern Shrimp Draft Amendment 4 Public Information Document (July 2024)

- Northern Shrimp Section Releases for Public Comment the PID to Draft Amendment 4 to the Interstate FMP for Northern Shrimp (June 2024)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section Virtual Meeting Scheduled for June 20 to Consider Approval of Draft Amendment 4 PID for Public Comment (May 2024)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section Maintains Fishery Moratorium for the 2024 Fishing Year and Initiates Amendment to Extend Moratorium and Implement Stock Monitoring Tool (December 2023)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Advisory Panel & Section to Meet to Review 2022 Traffic Light Analysis & Discuss the Future of Northern Shrimp Management (November 2023)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section Extends Moratorium on Commercial and Recreational Fishing Through 2024 (December 2021)

- Moratorium on Northern Shrimp Commercial Fishing Maintained Through 2021: Northern Shrimp Section Approves Addendum I to the FMP (November 2018)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section and Advisory Panel to Meet November 15 & 16: Section to Consider Final Action on Addendum I & Set 2019 Fishery Specifications (November 2018)

- Northern Shrimp Draft Addendum I Public Hearings Scheduled (October 2018)

- Northern Shrimp Benchmark Assessment Indicates Resource Continues to be Depleted: Section Approves Draft Addendum I for Public Comment (October 2018)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section to Meet October 4th to Review Benchmark Assessment Results and Consider Draft Addendum I for Public Comment (September 2018)

- ASMFC Schedules Peer Review for Northern Shrimp Benchmark Stock Assessment for August 14-16, 2018 (June 2018)

- Moratorium on Northern Shrimp Commercial Fishing Maintained for 2018 Season (November 2017)

- ASMFC Approves Amendment 3 to the Interstate Fishery Management Plan for Northern Shrimp (October 2017)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section and Advisory Panel to Meet November 29th to Consider 2018 Fishery Specifications (September 2017)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section Selects Final Measures for Amendment 3 and Recommends Final Approval by the Commission (September 2017)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section to Meet August 31st in Portland, ME to Consider Approval of Amendment 3 (August 2017)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section Approves Public Hearing Document on Draft Amendment 3 for Public Comment: New England States Schedule Public Hearings (March 2017)

- Northern Shrimp Data Workshop Scheduled For April 5-7, 2017 in Portland, ME (February 2017)

- Moratorium on Northern Shrimp Commercial Fishing Maintained for 2017 Season (November 2016)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section and Advisory Panel to Meet November 10th to Set 2017 Fishery Specifications (October 2016)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section Resumes Development of Draft Amendment 3 (June 2016)

- Moratorium on Northern Shrimp Commercial Fishing Maintained for 2016 Season (December 2015)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section Postpones Development of Draft Amendment 3 (September 2015)

- New England States Schedule Hearings on Northern Shrimp Public Information Document for Draft Amendment 3 (February 2015)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section Releases the Public Information Document for Draft Amendment 3 for Public Comment (February 2015)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section Establishes Moratorium for 2015 Commercial Fishing Season Draft Amendment 3: PID Approved for Public Comment (November 2014)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section to Meet November 5th to Consider Approval of Amendment 3 PID for Public Comment and Set 2015 Specifications (October 2014)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section Initiates Amendment to Consider Limited Entry in the Northern Shrimp Fishery (June 2014)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section Establishes Moratorium for 2014 Fishing Season (December 2013)

- ASMFC Begins Preparations for Northern Shrimp Benchmark Stock Assessment (March 2013)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section Modifies Landing Days for Trawl and Trap Fisheries & Removes Daily Limit in Trap Fishery (March 2013)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section Modifies Landing Days for Trawl Fishery (February 2013)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section Sets Specifications for 2013 Fishery (December 2012)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section Approves Addendum I to Amendment 2 to the Interstate Fishery Management Plan (November 2012)

- Understanding the Science Behind Northern Shrimp Management: ASMFC Northern Shrimp Technical Committee to Conduct Science Workshop on October 17 (September 2012)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section Approves Draft Addendum I for Public Comment (September 2012)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section Closes Fishery Effective 2359 Hours (EST) (February 2012)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section Revises 2012 TAC to 2,211 MT (January 2012)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section Revises Landing Days and Date of First In-Season Meeting (December 2011)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section Sets 2012 Fishing Season Specifications (November 2011)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Approves Amendment 2: Preliminary Assessment Results Indicate Need for Significant Harvest Reductions for 2011/2012 Fishing Season (October 2011)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section Closes Fishery Effective 2359 Hours (EST) February 28, 2011 (February 2011)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section Schedules Emergency Meeting to Consider Closing 2010/2011 Fishery (February 2011)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section Schedules Conference Call to Review Landings Data and Discuss Management Options (February 2011)

- 2010/2011 Northern Shrimp Fishing Season Set at 136 Days (November 2010)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section Closes Fishery Effective 2359 Hours (EST) May 5, 2010 (April 2010)

- ASMFC Northern Shrimp Section Schedules Emergency Meeting to Consider Closing 2009/2010 Fishery (April 2010)

- Northern Shrimp 2010 Fishing Season Set at 180 Days (October 2009)

- Northern Shrimp 2009 Fishing Season Set at 180 Days (November 2008)

- Northern Shrimp 2008 Fishing Season Set at 152 Days: Section Expresses Concern About Shrimp Availability During the 2009 Fishing Season (November 2007)

- Northern Shrimp 2007 Fishing Season Set at 151 Days: Section Tentatively Commits to a 2008 Fishing Season for Same Duration (November 2006)

- Northern Shrimp 2006 Fishing Season Set at 140 Days (November 2005)

- Northern Shrimp 2005 Fishing Season Set at 70 Days (November 2004)

- ASMFC Approves Amendment 1 to the Northern Shrimp Plan (May 2004)

- Nov 13, 2003 - Northern Shrimp 2004 Fishing Season Set at 40 Days (November 2003)